Image: Julia Klein, wearing a black tank top and smiling for the camera, poses at her booth at the New York Art Book Fair. Photo by Lisa Pearson.

I first encountered Julia Klein, artist and the publisher of Chicago-based Soberscove Press, at the packed art book fair at the College Art Association’s annual conference. A mutual friend introduced us, under the guise that we were both tied to the publishing industry but had our own creative practices: Julia as an artist and me as a scholar.

Now, several years later, we are regular collaborators in the editing process—having worked together on numerous projects. Throughout, I have found her to be a very generous colleague who is very devoted to her craft.

Founded in 2009, Soberscove Press is guided by Klein’s interests in collaboration, documentation, process, and the relationships between various forms of work within singular artistic practices. Many titles are based on archival research, artist’s writings, and historical dialogues, including the collected writings of sculptor Scott Burton, a diary and other related writings by Rosemary Mayer, interview transcripts with mail artist Ray Johnson and the restoration workers at the Acropolis in Athens, and archival documentation of pedagogic experiments in California in the late 1960s, among others, as well as numerous artists’ board books.

As an artist, Klein has exhibited her artwork nationally in venues including the International Museum of Surgical Science, Chicago Artists Coalition, Tiger Strikes Asteroid (Chicago); MOCAD and Wayne State University (Detroit); Vox Populi (Philadelphia); Shirley Fiterman Art Center/BMCC (NYC); Gridspace and Songs for Presidents (Brooklyn); as well as at the Terra Foundation for American Art (Giverny, France), among others. Klein has participated in a number of fellowships and residencies and is part of several ongoing performance and publishing collaborations with other artists and writers.

In what follows, we discuss the history of Soberscove, the intersection of art and publishing, and her advice for artists and academics hoping to publish more.

Cara Jordan (CJ): How did you get into publishing?

Julia Klein (JK): After college, I worked for the New York publisher George Braziller at his eponymous independent publishing house, which he ran for over fifty years. My undergraduate degree was in art, but Braziller was known for hiring young people and giving them enormous responsibility, so I began editing books after several months of working there. A proposal came in for a collection of writings by the second-generation abstract expressionist Robert Goodnough and, while Braziller was not interested, I was galvanized by a transcript Goodnough had edited of the abstract expressionists in conversation in 1950, which eventually became Artists Sessions at Studio 35. Around that time, I decided not to go to graduate school for art history despite my continued interest in archival research, and my research into the transcript became a way for me to engage with primary materials. Ultimately I published the transcript—my first publication—in 2009. With the umbrella of Soberscove now established, I decided to continue on this path, and the press and its mission have evolved ever since.

CJ: You were an artist before and now alongside running Soberscove. Do you think these two roles (artist/publisher) intersect? What does being an artist bring to the press?

JK: I see being a publisher and an artist as distinct roles that mutually inform one another. Each involves its own modes of working, types of responsibilities, forms of engagement with collaborators, and conceptions of audience. In my art practice, I’m invested in working physically with materials, which is quite different from the sitting-at-my-dining-room-table-tethered-to-my-computer nature of working on publishing books. The question of resolution—when is an object “finished” and what does “finished” mean—is important in my sculptural work; quite often I work with materials for years before the process comes to a final resting point, the end of the line in terms of its potential to be otherwise. This engagement with what it means to be “finished” is also an issue in terms of Soberscove’s publications, often in the context of larger discussions of process and documentation. This is an example of how my artistic sensibilities drive Soberscove’s content. With books, of course, there is a clear “done”—bringing a book to publication is a process of refinement that always results in a finished product. Not that this precludes books as things in flux but, for me, publishing involves a clear end goal, which is not always the case in my studio practice.

CJ: What’s your favorite part of the publishing process?

JK: Over the past year, my enjoyment of the editorial phase of the process grew immensely and I learned a great deal. This is currently my favorite part of the process, but I always enjoy getting the first draft of the layout, finally seeing all of the content laid out, and having something to respond to. Feeling like we’ve nailed the cover is a really great feeling too!

CJ: How would you characterize your editorial style?

JK: I used to be a lot less hands-on, in large part because I lacked confidence in what I could offer editorially. As I’ve accrued more positive editorial experiences, I’ve developed more confidence in asking questions as I work through a text—all of the why’s, how come’s, I-don’t-get-it’s, and that-sounds-funny’s. Usually I go through once and make tons of comments, and then I comb through them again and winnow them down as I start to understand the logic of the text and answer my own questions. I think every author I work with helps me to learn how to adjust to different styles and voices, and I feel like working with good outside editors and copyeditors also teaches me a lot—I’m always amazed at what they find that didn’t even cross my mind.

CJ: How do you choose projects?

JK: I don’t have a consistent formula. Here are examples of how recent books came to be: one was offered to me by someone I had worked with on smaller projects; one developed out of a conversation with a friend who told me about an exciting discovery he’d made and I said, “I think that’s a book!”; one developed out of a previous project—we decided that instead of doing a second edition, we would build a new project to continue the work of the first book; one was proposed to me by someone whom I didn’t know at all, but I thought the project was fascinating.

CJ: What’s coming up in your catalogue that we should be ready for?

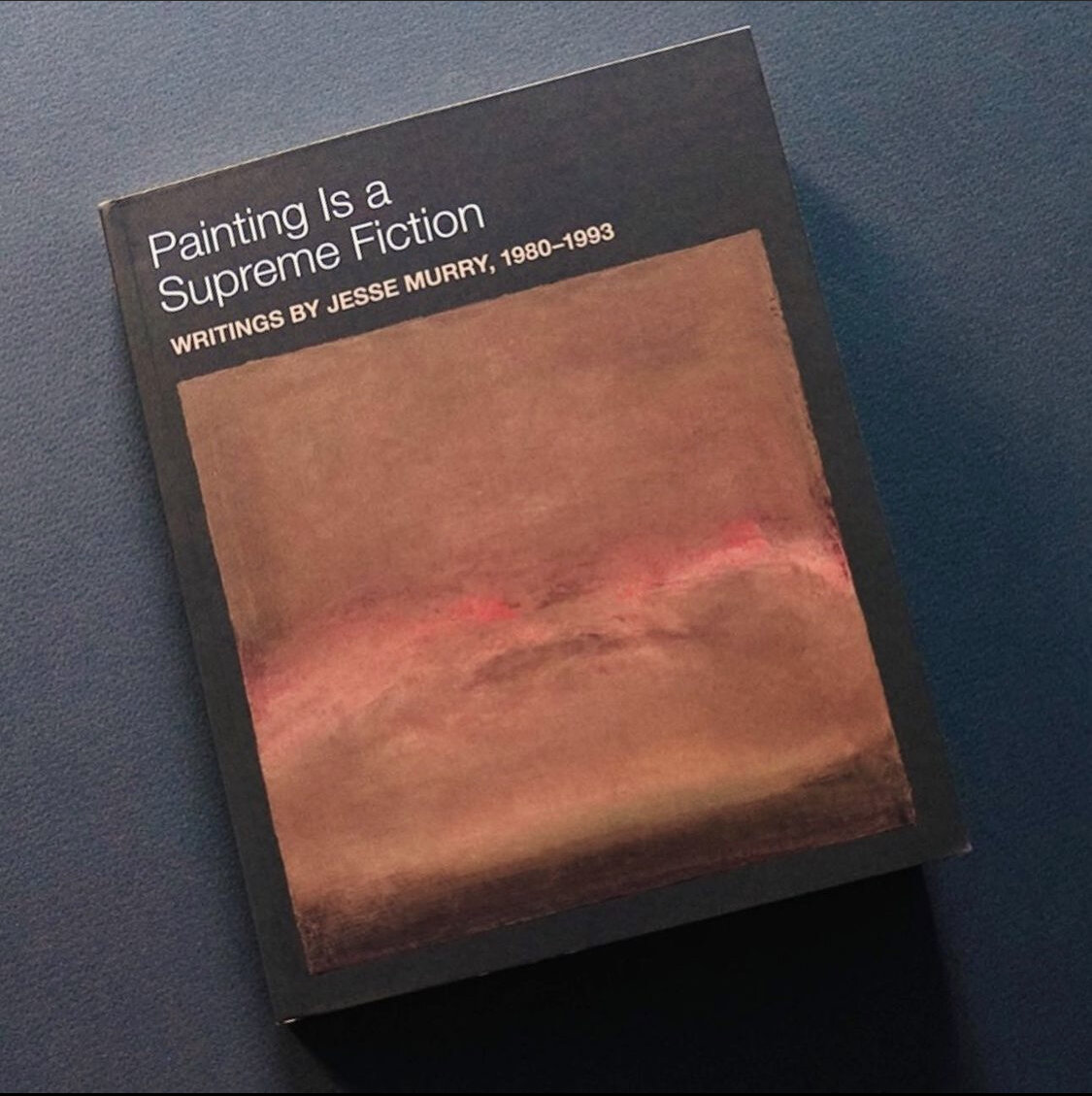

Image: The cover of one of Soberscove’s upcoming titles: Painting is a Supreme Fiction, Writings by Jesse Murry, 1980–1993, edited by Jarrett Earnest with foreword by Hilton Als, which has an abstract, colorfield painting in subdued warm, neutral tones at its center.

JK: I’m super excited for the two books coming out this fall: Painting Is a Supreme Fiction: Writings by Jesse Murry, 1980–1993, edited by Jarrett Earnest with foreword by Hilton Als, is a collection of writings (criticism, essays, poetry, notebook transcriptions) by Murry (1948–93), an incredible and underrecognized artist and thinker who died way before his time, just as he was hitting his stride as a painter, as result of AIDS-related illness. In Rip Tales: Jay DeFeo’s Estocada and Other Pieces, Jordan Stein tracks the material history of a little-known, undocumented, and destroyed artwork in tandem with the artistic evolution of its maker, Jay DeFeo, interwining this narrative with shorter writings and interviews that draw out other hidden Bay Area art stories of the last sixty years (on artists including Ruth Asawa, Lutz Bacher, and Bruce Conner).

In the winter, there are two books rooted in collaboration. In Wolf Tones, artists Max Goldfarb, Nancy Shaver, and Sterrett Smith open their ongoing engagement with the acoustic phenomenon of the wolf tone to include contributions from nine new collaborators from a wide range of fields alongside their own. And Lastgaspism: Art and Survival in the Age of Pandemic by Anthony Romero, Daniel Tucker, and Dan S. Wang picks up on themes in a previous book they did with Soberscove (Organize Your Own) to explore art and activism that engages with the interlocked crises of our present moment.

CJ: Given that we’re living the full digital life at this point and there are fewer opportunities for projects to develop organically from in-person interactions or from discussions at a book fair, do you have any tips for authors/editors who have a project they want to pitch to a publisher by email?

JK: Personally, I think it’s crucial that a potential author/editor review the list of the publisher to whom they’re writing and that they make a case for why their book makes sense in the context of that publisher’s catalogue. If someone writes me a personalized email about a project that they feel fits with my list, I will write them back a personal response and try to be helpful if I can. (While I am open to proposals, it’s rare that books happen this way because I publish relatively few books and so many develop out of existing relationships.) If someone writes to me about a project that clearly has nothing to do with what Soberscove publishes, I just think why? I’ll write back, but it’s always kind of a bummer.

CJ: What advice would you give an artist who wanted to publish their own book?

JK: I think an initial thing to think about is to ask yourself what does “publish” mean to you? A definition of “publish” is “to prepare and issue (a book, journal, piece of music, etc.) for public sale, distribution, or readership”—so there is a big range of what publishing a book could look like. Do you want to and/or are you willing to do the project on your own, no matter what, or do you want/need some other entity to produce and/or fund and distribute it for you? What kind of book are you thinking about—something inexpensive, maybe zine-like, or something more elaborate and/or handmade (and the whole spectrum in between)? What are your ambitions in terms of circulation and who do you think your audience is (and do you care?). How much autonomy/collaboration do you want to have? Then there’s the perennial issue of distribution… There’s a lot to be learned from artists who make books as part of their practice (and from publishers who primarily work with artists). I feel like people in this realm are very generous and, if you look even casually, you can find a ton of resources that share ideas and offer ways of thinking about the artist as publisher.