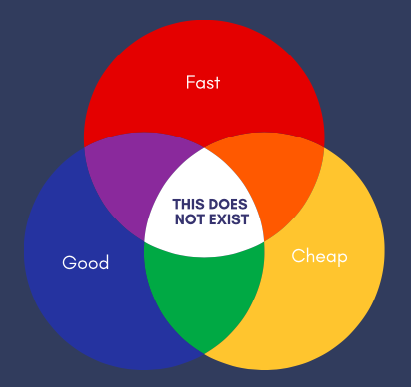

Image: Venn diagram of three intersecting circles, labeled “Fast,” “Cheap,” and “Good,” all of which intersect in the middle, which says “This does not exist.” The three circles are primary colors, where they intersect are secondary colors, and the center is white. Image by the author.

That little phrase “all translations are my own” can be an academic point of pride, a flash of intellectual glamour. You’ve spent years learning foreign languages to do your work, now you can show off the results!

But is it always a good idea to translate quotations or other texts from your sources yourself? When does it highlight your skills and when does it lead you into dangerous waters?

There are no rules for when to do it or not, but if you’re weighing the choice, there are a few basic questions you should ask yourself:

1. Has someone else already translated this?

Search online and check databases to see if a translation already exists—even a partial one or one from an earlier decade or century—because an existing translation of a text has a lot in its favor. First, it’s almost never worthwhile to translate a passage yourself if your reader can consult the whole passage, or even the whole text, in a translated standard edition with all the notes and supporting materials it offers.

And, while you might feel you should translate a text yourself because others before have missed some nuance, you want to avoid the impression that you don’t know that other translations exist. And, as we’ll see below, it might be more trouble than it’s worth.

Think about your readers, too. Do they need this particular detail that only your translation can provide? And, finally, will referring readers to a source that’s not in English be helpful or not?

2. Is the original from another historical period, regional dialect, or linguistic subgroup?

If it’s an older text, you’ll need not only your usual reading skills but also familiarity with period vocabulary and distinctions in terms and usage. This is particularly relevant when you feel your translation would improve on an outdated one. The eighteenth-century translator of an eighteenth-century text, for example, may have matched the original very well and your modernized version could actually misrepresent the usage of certain period terms.

These same considerations also apply to specific cultural contexts—Are you the right expert to translate Japanese skateboarder slang or naughty Neapolitan drinking songs into English? Consider whether you have the depth of linguistic expertise needed for the text in question.

3. Can your translation speak the language of the discipline?

When it comes to academic texts, you’ve probably already noticed that some terms are normally left untranslated, some have a standard translation, some have been anglicized, and a few have generated entirely new words in English.

The biggest mistake you can make is to create your own translation, ignoring how others have translated these concepts in the past. Take the time to do your research on the text you’re translating and find references to the terms it uses and the most common translations for them. In addition, if certain concepts are associated with the text’s author, be sure you know which ones and how to refer to them.

4. Can your translation match the text’s genre and style?

Stylistically distinctive texts are challenging. If you aren’t prepared to translate a poem or a song lyric into an appropriate form in English, you might serve your reader better by paraphrasing or explaining it instead.

Even when the source is an academic text, its conventions may not match English academic standards. Unraveling complex sentences and then knitting the ideas back together in English will take considerable effort. That leads to the next point.

5. Do you have the time?

This seems obvious, but translation adds another layer of work onto the writing project you already have going. You’ll need to translate, do the appropriate research, revise your translation, and then recheck it against the original to make sure you haven’t missed anything along the way.

And if you submit a translated text without the original, no editor can catch your mistakes (and we all make mistakes). Always plan extra time for translation tasks.

6. Do you know when to ask for help with your translation?

Professional translators run into tough questions all the time relating to all of the issues listed here. Good translators use multiple dictionaries, they turn to their colleagues for group wisdom, they email the author when they can, they post questions in translators’ forums, and they ask for help from experts in the relevant disciplines.

Translators joke that a translator is someone who finds translation more difficult than other people, and there’s truth to that. Above all, they aren’t afraid to recognize their own limits.

Of course, if you want to translate an entire article or presentation, these problems will be multiplied.

So go ahead and show off your language skills, but only when it makes you and your ideas look your best!